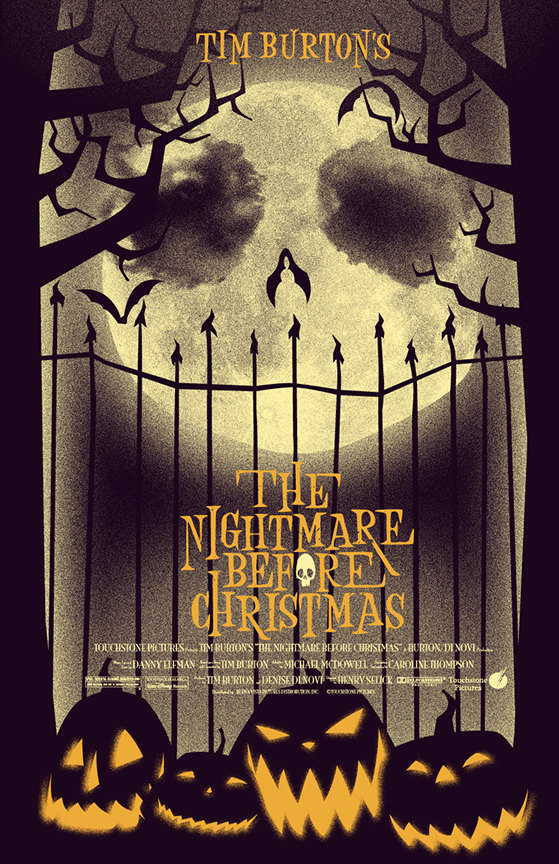

Halloween is coming and Pumpkins with ghoulish faces and illuminated by candles are a certain sign of the Halloween season. It’s a good opportunity for us to talk about the origins of the presence of pumpkins in the festival of the dead.

As a quick reminder, Halloween is the evolution of the Celtic festival of Samhain that celebrate the end of the year and the entrance in the new one with three to five days in-between that are out of calendar and belong to the spirits. Replaced by the Christians, it became the celebration of their saints and, in general, of the deceased.

But for today, let’s only focus on the importance of pumpkins in Halloween.

It was not until the 19th century, during large waves of immigration from Scotland and Ireland that Halloween became popular in the United States, only to be truly celebrated throughout the country during the first decade of the 20th century. It was also during this period that the first versions of the now traditional Jack-o’-lantern (or Will-o’-the-wisp, the famous pumpkins emptied and carved before being illuminated by a candle) appeared in Ireland and then in Scotland. Contraction of “Jack of the lantern” and “Will of the wisp”, their meaning varies from their origin, because, according to the creator, they either represent monsters or the spirits of the dead and are exposed either to protect themselves from the spirits or to frighten overly enterprising visitors.

In 1937, the Irish newspaper Limerick Chronicle already spoke of a competition in a pub for the best “crown of Jack McLantern”. And we could surely go back even further to the origin of this tradition since, in 1856 in his book The British, Roman, and Saxon antiquities and folklore of Worcestershire, the folklorist Jabez Allies speaks of his childhood (he was born in 1787) when the children of peasants carved “Hoberdy’s Lanterns” from turnips before lighting them up to chase away travelers and wanderers who spent the night. Indeed, if today we only carve pumpkins, during the 19th century, they carved turnips, gourds or squash according to social origins.

Will-o’-the-wisp is just one English name for wisps, like Jack-o’-lantern, friar’s lantern, hobby lantern and hinkypunk. “Wisp” originally designating a torch made of an assemblage of rapidly burning materials, the name “Jack with the lantern” was actually a variation of “Will with the torch” which designated various very brief natural phenomena such as lightning balls, St. Elmo’s fire, static electricity and ignis fatuus (modern Latin literally translated as “mad fire”). All these phenomena were attributed to fairies and mocking/evil spirits and were perfect to worry rural populations where they were often present at night. In particular, will-o’-the-wisps (or ignis fatuus) which manifest themselves thanks to the released gas from poorly isolated decomposing corpses. In the countryside and cemeteries of the time, they were therefore much more common than nowadays when this phenomenon has become even rarer than it already was.

Still according to Jabez Allies, the first name Jack would meanwhile come from a tale where a young man manages to trap the devil by tricking him. Jack then releases him against the promise to never take his soul. However, once dead, Jack does not go to heaven because he is too bad, but Satan also refuses to welcome him in hell since he has sworn to not take his soul. To mock him, Satan only gives him an underworld flame that will never go out so that he can orient himself. Jack therefore cuts a turnip to lodge his flame there and goes wandering for eternity with his lantern in order to reach a place where he can finally find rest.

However, although reliable sources are difficult to find, this name was probably used as early as 1660 to refer to guards patrolling at night before becoming a synonym for the Will-o’-the-wisp a few years later. However, it can be found in writing as early as 1704 in Jonathan Swift’s social satire A Tale of a Tub: “Sometimes they would call Jack the Bald; sometimes Jack with a lantern; sometimes Dutch Jack”.

These days, the spirit of Halloween is usually personified as a pumpkin-headed humanoid named Jack-o’-lantern. This imagery is actually from adaptations of the short story The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820) by historian and novelist Washington Irving.

The Headless Horseman, ghost of a German mercenary beheaded by a cannonball during the War of Independence and seeking his lost head, has been associated with Jack-o’-lantern in most of his film adaptations (or in the illustrations of the short story) because he was represented either carrying one to light up at night, or as a replacement for his head. The idea came from the original text where a crushed pumpkin is found where the main character met the Headless Horseman the day before. We can find this image in particular in the second story of the 1949 Walt Disney feature film The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad.

This portrayal has since become firmly entrenched in popular culture and now, it’s hard to imagine Halloween without a pumpkin. So enjoy it and take the opportunity to sculpt your own according to the origin story that inspires you the most.

Today’s article was a bit peculiar since it is actually an excerpt from a more detailed study on Halloween carried out in 2018. For those who want to know more about the origins of this special holiday, you can read the full original article on the website of the author: Historia Draconis.